Best Picture of 1940

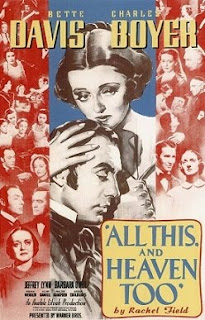

I'm now back in New York City after an exciting summer in Pennsylvania. My busy schedule during that time meant that reviewing this current selection of Best Picture nominees took well over two months, but after a much-needed recap of my musings, I'm now ready to make my decision on which of these entertaining films is most worthy of the top award. The nominees for Best Picture of 1940 are: All This, and Heaven Too Foreign Correspondent The Grapes of Wrath The Great Dictator Kitty Foyle The Letter The Long Voyage Home Our Town The Philadelphia Story Rebecca There's something to admire in each of these ten pictures. They all capture their respective moods very nicely, some more than others. A few have a slightly inconsistent atmosphere, though. In Foreign Correspondent, Hitchcock occasionally shines with some thrilling scenes, but not consistently enough for my taste. The Long Voyage Home contains some gripping sequences but feels disjointed as a whole. Likewise, Our Town ha...