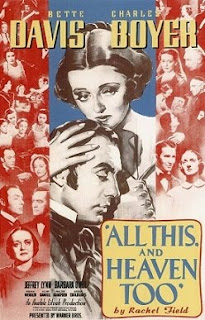

1940 - All This, and Heaven Too

It is undoubtedly summer in Pennsylvania. This week, the heat has been almost unbearable, topping 38 degrees Celsius, which sounds much more powerful and effective when expressed in Fahrenheit: It's a hundred degrees! As I write this, the weather gadget on my computer desktop is displaying the temperature in Boiling Springs as N/A. I can only assume that the intense heat has broken the recording instruments. Yesterday, I remained indoors as much as possible, where I watched another film from the selection of 1940's Best Picture nominees... All This, and Heaven Too Director : Anatole Litvak Screenplay : Casey Robinson (based on the novel by Rachel Field) Starring : Bette Davis, Charles Boyer, Barbara O'Neil, Jeffrey Lynn Academy Awards : 3 nominations 0 wins Mademoiselle Henriette Deluzy (Davis) is the new French teacher at a girls school in mid-nineteenth-century England. Her first day is marred by taunts from her impudent students, who have heard rumours that their teacher...